What do we mean when we say that someone is a key opinion leader (KOL)? That they are an expert in their field? That they are a frequent publisher or speaker? That they influence clinical practice through positions with international or national organisations? Is an opinion leader someone who knows importance of social networks and has extensive social connections with their peers through which they exert influence? Or someone held in high esteem by their peers? I’d argue that all of the above are important when identifying and engaging with KOLs. In this blog, however, I want to look at one particular dimension of opinion leadership; social connectivity and network analysis, and how these relate to KOL identification and engagement.

Information and influence in importance of social networks

The social relationships between people are important in the development and spread of new ideas because of two principles:

- Rather than make up their own minds when presented with information, individuals look to their social network to decide whether to adopt a new idea or not.

- Information and ideas flow through a population of people through social interactions.

Key opinion leaders are those who are connected, either directly or through intermediaries, to many others in a network. Their social connectedness means they receive new and diverse information and ideas and are therefore more knowledgeable than others. Their own thinking and ideas also have greater reach within a social network.

Social network analysis – the study of the relationships between individuals – is therefore a brilliant tool for identifying, understanding, and engaging with, KOLs. Social networks are not just some dry theoretical construct but a vital force in the development and acceptance of new ideas and thinking. To demonstrate the importance of social relationships in the development and spread of ideas, we’re going to look at how the most important scientific theory ever came to be developed.

Edmund Halley, Isaac Newton and Newton’s three laws of motion

In 1684, 28 year old Edmund Halley was the astronomy community’s brightest young star (the comet is named after him). He knew or corresponded with nearly all the great minds in European science; he had worked with the great Belgium astronomer Johannes Hevelius; he was assistant to the Astronomer Royal John Flamsteed, and, when he wasn’t working on his lunar observations, spent his time discussing the latest ideas and theories with fellow members of the Royal Society. It was in one of these London coffee house discussions in January 1684 that he posed the question which led to the publication of the most important book in history of science. While discussing the dynamics of planetary motion, Halley asked two friends, Christopher Wren and Robert Hooke, if the force that kept the planets moving around the sun could decrease as an inverse square of the distance? Wren and Hooke laughed. The ‘inverse square law’ was not a new concept: it was the principle upon which all the laws of celestial motion were established. The problem was that nobody had found the mathematical means to prove it. Wren confessed that he had been working on the proof for some time himself but without success and, eager for a solution, he offered a cash prize to whoever could provide the proof. Hooke said that he had already proved it and that he would provide the calculations in two months’ time.

Seven months later, however, when neither Hooke nor anyone else had produced the proof, Halley decided to look elsewhere for the answer. There was an academic in Cambridge who had a reputation for scientific and mathematical genius, and Halley thought it worth discussing the problem with him. He knew the man was a recluse who rarely communicated with the rest of the scientific community, so rather than write to him and receive no reply, Halley decided to meet him in person.

Which is how, in August 1684, Halley ended up sitting in a study at Trinity College, discssing planetary motion with Isaac Newton. Halley asked Newton what curve would be made by the planets around the Sun ‘supposing the force of attraction towards the Sun to be reciprocal to the square of their distance from it’. Newton immediately replied that it would be an ellipse. Halley, ‘struck with joy and amazement’, asked him how he knew this. ‘Why’, said Newton, ‘I have calculated it’. But Newton had carried out these calculations almost 20 years previously, when he was a student, and now couldn’t find them. So Halley made Newton promise to do the calculations again and send him the proof. Two months later, Newton sent Halley De motu corporum in gyrum, which proved the ‘inverse square law’ and Halley arranged and paid for its publication himself. But Newton didn’t stop there: in 1687, he sent Halley a further work, Philosophiæ Naturalis Principia Mathematica, which extended Newton’s work on the movement of planets around the sun, into a general theory of celestial motion.

Halley, Newton, information and influence

The development and spread of new ideas is not simply great minds experimenting and theorising. The great minds do experiment and theorise but they don’t do it in isolation, there is a social dimension to scientific discovery. Within this social dimension individuals receive information and spread influence.

We can see the importance of social relationships for the flow of information. Halley’s thirst for ideas and knowledge can be seen through the diverse relationships he has within the scientific community – Hevelius, Flamsteed, Wren and Hooke – he likely isn’t influencing these people, but he has learnt from them. Unsatisfied with the knowledge offered by his coffee house clique, Halley went looking for information elsewhere through a different social connection (an example of the concept of weak-ties, that communication between close and similar associates is easy and frequent, but that it is the communication between dissimilar associates, so-called weak-ties, that is often the most crucial in the diffusion of innovation). And the meeting between Newton and Halley in Cambridge is vital because Newton learns that the scientific community wants this proof.

But relationships aren’t just a tool by which information flows, they are also a way that information and ideas are validated by opinion leaders. Halley already has the idea of the ‘inverse square law’, but it is only because Wren and Hooke confirm its importance that he goes on his quest to find the proof. For Newton, his ideas only become known to the scientific community through his relationship with Halley. Halley publishes the two books and through his influence makes sure that Newton’s ideas become known. It is important to recognise though that social influence isn’t the only type of influence. Generally the individuals who are most esteemed for their expertise are also the most socially connected both because their social connectedness fuels their expertise and also because their expertise attracts ever more social connections. However, it is not always the case. If we had conducted a social network analysis of English natural scientists at the beginning of 1684, then the esteem that Newton was held in by his peers wouldn’t be apparent. He would have seemed far less important than countless members of the Royal Society who the world has long forgotten.

What social network analysis can tell us about opinion leaders

By studying social relationships, we can understand the flow of influence and information through a social network. The position of an individual within a network can also tell us a lot about their influence, who influences them, and their attitude to new ideas and information. This is to some extent a matter of interpretation rather than black and white answers, which is why we always recommend to clients that social network analysis is accompanied with a face-to-face consultation and interpretation session. However, there are some common positions that individuals have within networks that can tell us a lot about the type of opinion leader they are, and how to engage with them and the network.

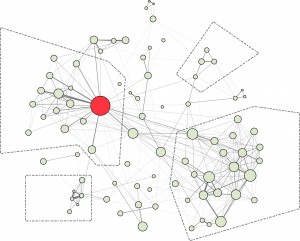

Central Hub

In the network map above, the circles are experts, and the lines between them social relationships. The social-connectedness of each expert, their centrality to the network, is calculated. The larger the circle, the higher their centrality. The red circle above is the most well-connected individual in this network and they are so well-connected that all other individuals seem to fan out from this one central hub, like spokes from a wheel. This particular individual is likely to influence the rest of the network to a huge extent. When engaging with this disease area, the overwhelming influence of this one individual would mean that they would need to be central to any engagement strategy. In particular, the individuals most closely connected to the central hub, the cluster encompassed by the dotted line, are likely to all hold very similar views to the central hub – useful to know when planning advisory boards and other activities seeking feedback.

Broker

The two individuals highlighted in red above are the bridges by which information travels between the two most important clusters in this social network. There are several individuals who have more extensive connections than these two within the network (we can tell from the size of their circles) but their position at the cross-roads of the flow of information means they are likely more important than anyone realises. Like Edmund Halley, their diverse relationships mean that they are interested in new and different ways of thinking. When planning how to engage with this network, we would emphasise:

- Their importance is likely only apparent through social network analysis, they are therefore hidden opinion leaders;

- They are probably early adopters, who are open to new ideas and thinking;

- And because they are open to new information, when providing feedback they are likely to supply information about the latest ideas.

Boundary Spanner

n the network above, there is one cluster of individuals, on the right, that appears to dominate the whole disease area. Because the individuals within this cluster are highly interconnected, we can conclude that they are heavily influenced by the thinking of their peers, probably to a far greater extent than the individuals outside the cluster. Often the most well-connected individual within the cluster, the central hub, is the bridge by which new ideas and information flows into the cluster, but that isn’t the case here. In the same way that Halley was on the edge of the clique of London scientists, part of the group are also looking outwards. In the network above the two individuals highlighted in red are on the edge of the cluster, but also the means by which new information is introduced. When seeking to engage with this cluster, it is worth knowing that these two individuals are likely to be the most open to new ways of thinking.

Structural holes in a network

A social network is the means by which the development and diffusion of new ideas takes place. Some networks are more conducive to the diffusion of innovation than others. A few months ago we conducted an opinion leader identification project for a client. One doctor was a clear opinion leader: he had published many influential and well-respected articles, was a member of a national society’s advisory board and, when we interviewed his peers, was always mentioned as someone whose opinion they respected. However, when we conducted social network analysis of the disease area, we could see that this opinion leader (lone red dot on the left of the map) was socially isolated from the rest of the community, in particular from the cluster in red on the right. Like Newton he had authority, but he didn’t exercise that authority through personal interaction, which is why his centrality score is low and his circle small. We therefore recommended to our client that they ‘fix’ the social network by providing a connection between the lone opinion leader and the dominant cluster. This would make the social network more conducive to the development and spread of ideas. This may seem a small thing, but if Halley had not fixed his social network by establishing a relationship with Newton, we may never have heard of Isaac Newton at all.

This is a flavour of how social network analysis can be of benefit when identifying and working with opinion leaders. Far from being some dry scientific theory, analysis of importance of social networks can bring you closer to the opinion leaders you engage with.