Opinion Leadership Demystified: Knowledge That Can Be Applied to Every Industry in 2025

Modern writers often depict opinion leaders as intermediaries between media and the public in the adoption of products, services, ideas, behaviours, or beliefs. However, this definition is overly restrictive, for opinion leaders transcend traditional boundaries.

They manifest as individuals whose choices, be it in products, services, ideas, behaviours, or beliefs, reverberate, influencing the decisions of others.

Opinion leaders are omnipresent, from individuals like Ryan of Ryan’s World shaping children’s toy preferences to Chris Van Tulleken translating complex research on ultra-processed food and presenting it in a way that has become part of Britain’s national discourse.

In healthcare, the pivotal role of engaging with Key Opinion Leaders (KOLs) cannot be overstated.

However, opinion leadership is often characterised as a malevolent, capitalist force, corrupting our inherently noble and rational decision-making process, and making people buy products and services they don’t need or that are contrary to their best interests.

Such a view is simplistic and, I think, springs from the mistaken belief that decision-making would be a fundamentally rational process without the influence of opinion leaders.

Not only is this not true, but we will see how in many situations the rational response to a decision is to look to an opinion leader for guidance.

To understand opinion leadership, we therefore need to understand how people make decisions, and why some innovations, ideas, beliefs of products take-off, and others don’t.

The following exploration will therefore unravel the intricacies of why we make the decisions we do and the role of opinion leaders in shaping society.

We will then look at how you can use this understanding to shape your marketing strategy and work with opinion leaders.

Origin of the Concept: Seeds of Opinion Leadership

The roots of opinion leadership reach down to the work of agricultural sociologists in the 1940s, notably Bryce Ryan and Neal Gross. Their study on corn seed adoption (1943) in Iowa sought to understand why farmers were slow to adopt a new, obviously superior corn seed.

Ryan and Gross discovered that farmers embraced innovations only when influential figures within their social networks did so — these figures became the keys steering the shift in opinions and behaviours.

Similar phenomena were observed in the medical field by Coleman, Katz and Menzel (1966); adoption of tetracycline among medical doctors was a social decision, shattering the then prevailing view that such decisions in medicine were purely rational and based on data.

Coleman, Katz and Menzel discovered that doctors who had more interpersonal relationships and networks, were quicker to adopt than those that didn’t.

Everett Rogers noted that this showed “that the diffusion of an innovation is essentially a social process that occurs through interpersonal networks.”

These seminal studies laid the foundation for understanding the social dynamics that govern decision-making.

Social Dynamics in Decision-Making: Beyond Rationality

Malcolm Gladwell, in his ‘Revisionist History‘ podcast, reflects on basketball legend Wilt Chamberlain’s perplexing decision to switch from an underhanded free-throwing technique to the overhand throwing technique favoured by all basketball players.

Chamberlain was a giant man. In his first two seasons in the league, the only way to stop Chamberlain was to foul him; Chamberlain was a terrible free thrower.

In 1962, Chamberlain decided to shoot his free-throws underhanded, the so-called “granny shot”, and he averaged over 50 points per game over the season (the highest non-Chamberlain average across NBA history is Jordan’s 37.1 points per game in 1986-87).

Experts argue that the underhanded free-throw is a better technique, it certainly was more successful for Chamberlain.

But the next season he went back to shooting overhand and became a terrible free thrower again. Chamberlain recognised it was the wrong decision but said “I felt silly, like a sissy, shooting underhanded. I know I was wrong.”

Gladwell argues that “Wilt Chamberlain’s brilliant career was marred by one, deeply inexplicable decision: He chose a shooting technique that made him one of the worst foul shooters in basketball—even though he had tried a better alternative.”

Chamberlain’s decision is not inexplicable though, it is only irrational, it is a deeply human decision that demonstrates the social nature of decision-making. People frequently make decisions to fit in with a social dynamic, rather than from a rational analysis of benefit.

Researchers, building on the work of Ryan and Gross, developed theories such as the two-step flow of communication, diffusion of innovation theory, social network theory, and The Structure of Scientific Revolutions.

While diverse in their approaches, these theories share a common thread — an acknowledgment that human decision-making is profoundly influenced by social dynamics.

Opinion Leaders and The Two-Step Flow Model of Communication

In 1948, Paul Lazarsfeld, Bernard Berelson, and Hazel Gaudet formulated the two-step flow model of communication, challenging the view that mass media outlets were dominant in shaping public opinion. They argued that mass media content first reaches “opinion leaders” — active media users who interpret and disseminate meaning to less-active consumers.

Elihu Katz further refined the theory, outlining three key attributes that characterize opinion leaders:

1. Expression of Values

Opinion leaders are individuals who openly articulate their values and beliefs. They are not hesitant to communicate their opinions on various subjects. This quality makes them influential, as others look to them for guidance and direction.

2.Professional Competence

Opinion leaders possess expertise and competence in their respective fields. They are knowledgeable and well-informed, which enhances their credibility. Their professional competence contributes to the trust that others place in their opinions and decisions.

3. Nature of Their Social Network:

The social network of opinion leaders is crucial. These individuals are well-connected within their communities or industries. The nature of their social network involves having influence over others and being positioned at the centre of information flow. This central position enables them to disseminate opinions effectively.

Examples that support this two-step flow model of communication abound, from prominent teachers on Twitter translating cognitive science into teaching methods, to Chris Van Tulleken bridging the gap between the science of ultra-processed food and public knowledge.

Opinion Leaders and The Diffusion of Innovations Theory

Building upon the foundations laid by Katz and Lazarsfeld, Everett Rogers introduces the Diffusion of Innovations Theory, a compass for understanding how, why, and at what rate new ideas and technologies spread.

Everett Rogers’ Diffusion of Innovations theory identifies five main elements that collectively influence the spread of a new idea within a society or social system:

1. The Innovation Itself

The nature of the innovation is a critical factor. Rogers emphasizes that certain characteristics of an innovation can impact its adoption rate. Innovations that are perceived as more advantageous, compatible with existing values, easy to understand, and easy to test are more likely to be adopted quickly.

2. Adopters

Adopters are the individuals or entities within a social system who decide to accept and use the innovation. Rogers categorizes adopters into five groups based on their adoption behaviour: innovators, early adopters, early majority, late majority, and laggards. The characteristics and behaviours of these adopter categories influence the overall diffusion process.

3. Communication Channels

Communication channels are the means through which information about the innovation is transmitted within the social system. These channels can include mass media, interpersonal communication, social networks, and various forms of communication technology. The choice of communication channels affects the speed and reach of the diffusion process.

4. Time

The element of time is crucial in understanding the diffusion process. Innovations take time to move through the stages of adoption, and the rate of diffusion varies. The timing of an innovation’s introduction, as well as the rate at which it is adopted, can be influenced by external factors, societal trends, and the context in which it is introduced.

5. The Social System

The social system encompasses the overall structure and dynamics of the community or society in which the innovation is introduced. Social norms, values, traditions, and existing networks all play a role in shaping how an innovation is received. The social system provides the context within which the other elements interact and influence the diffusion process.

Rogers argues that early adopters, or opinion leaders, play a pivotal role, influencing the early majority to embrace innovations. These leaders, characterized by higher social status, financial liquidity, and advanced education, guide the narrative, fostering the acceptance of groundbreaking ideas.

Rogers illustrates the theory through a study by Wellin (1955) on the unsuccessful adoption of a health scheme in a Peruvian village. The scheme aimed to limit the spread of typhoid and other water-borne diseases by encouraging people to boil water before drinking it.

Despite the step needed to make water safe, boiling it, being straightforward and easy, only 11 of 200 households adopted the practice.

The health worker advocating for the scheme lacked the respect of the villagers and the scheme was contrary to social norms, underscoring the theory’s key conclusions: decision-making isn’t rational but is profoundly influenced by social norms, and key opinion leaders are indispensable for the acceptance of beneficial innovations.

Opinion Leaders and Social Network Analysis

Durkheim and Tönnies began researching social groups in the late 19th century, and there were other sporadic examinations of social structure over the next 100 years or so, but it was in the age of the internet and social media, that social network analysis took centre stage, offering ways to examine the structure of networks, relationships, and the influence they have on beliefs and decision-making.

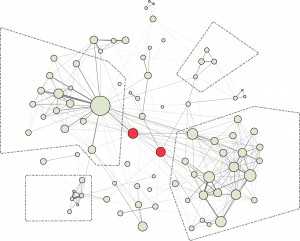

Social network analysis examines human society as a series of nodes, with each node representing an individual in the network, and ties or links representing the relationships between individuals. creating a map of social influence.

Analysis of social network maps can reveal important information about the networks, and about the individuals within those networks.

As Coleman, Katz and Menzel discovered in 1966, those with more interpersonal networks and relationships adopt innovations sooner than those who don’t.

Rogers characterises early adopters as opinion leaders.

Examination of a network map therefore allows us to identify opinion leaders by identifying the individuals with the greatest interpersonal connectivity. Furthermore, we can also identify structural holes in networks, and individuals who are boundary-spanners, lifting our ability to precisely engage with individuals within a network (see ‘The importance of social networks in the spread of ideas’).

Mapping the social network also aids in understanding the dynamics that shape the acceptance or rejection of innovations.

Innovations do not spread rapidly through social networks where individuals are tightly interconnected, whereas social networks where individuals have disparate and varied social relationships see a more rapid spread of new ideas.

In the Wilt Chamberlain example of social decision-making explored by Gladwell, Chamberlain knew his underhanded shooting technique was more successful, and yet the social norms of his network, a belief that underhand shooting was for “grannies”, caused him to adopt a less successful technique.

And while the Wellin study of the adoption of water-boiling in Peru did not conduct a detailed examination of the social relationships within the village, social network theory helps us understand the likely reasons why the health worker was unsuccessful in introducing this life-saving idea to the village:

- The social network of the village was likely highly interrelated with individuals having few relationships outside of the village – social network theory argues that such networks are less open to innovations.

- The health worked failed to engage with the key opinion leaders in the village.

- The idea of boiling water before drinking was contrary to the social norms of the network.

Opinion Leaders and The Structure of Scientific Revolutions

Thomas Kuhn’s groundbreaking work, “The Structure of Scientific Revolutions,” published in 1962, challenged the traditional notion of scientific progress as a steady accumulation of facts and theories.

Kuhn proposed an alternative perspective, introducing the concept of paradigm shifts and revolutionizing the way we understand scientific development.

Kuhn’s theory suggests that scientific progress is not a linear, continuous process but rather occurs in episodes characterized by periods of conceptual continuity, known as “normal science.”

These episodes are punctuated by moments of revolutionary science, where a new paradigm emerges, reshaping the scientific community’s fundamental ways of thinking.

In contrast to the rational image of science, Kuhn’s theory stirred controversy by asserting that paradigm shifts are not entirely rational processes.

The adoption of a new paradigm involves a shift in the fundamental assumptions and frameworks guiding scientific thought, challenging the prevailing rationality of scientific progress.

What does Kuhn’s theory suggest about opinion leadership and the dynamic social nature of decision making?

While Kuhn did not conceive of his theory applying to cases such as the health intervention of boiling water in a Peruvian village, his theory is another lens through which we can understand decision-making and opinion leadership.

Wellin noted that there was an existing paradigm in the village that boiling water was reserved for the unwell.

Kuhn did not talk about opinion leaders as such, but as we have already seen, they are often viewed as translating complex information and communicating it in a way that is compatible with the ways of understanding of their audience.

Kuhn’s theory argues for a paradigm shift in the Peruvian village, but perhaps an opinion leader would have been able to introduce the idea of boiling water to remain healthy, in a way that was consistent with the village’s belief about boiling water being for the unwell, rather than as something contrary to it.

Thomas Kuhn’s theory of scientific revolutions provides a powerful framework for understanding the dynamics of progress and change within scientific communities.

By applying Kuhn’s concepts to real-world examples, such as the challenges faced in introducing new health practices, we gain insights into the role of paradigm shifts and the importance of opinion leaders in navigating these transformative moments.

What Do These Theories Tell Us About Opinion Leaders?

Exploring these theories has allowed us to better understand opinion leaders and opinion leadership.

Opinion leaders:

- Are respected figures within their social networks.

- Are endowed with judgment, principles, and high social status.

- Reshape information to align with prevailing beliefs.

- Leverage their extensive networks for influence.

- Rely on personal judgment rather than conformity when making decisions, positioning them as catalysts for change.

Opinion Leadership: From Theory to Practice

Having explored these fascinating theories about the opinion leaders and opinion leadership you may be asking you what you should take from them. Key things for you to remember.

- Opinion Leaders are vital in any decision-making process, whether you choose to engage with them or not.

- Opinion Leaders are a natural part of social decision-making and not a malignant force.

- You cannot rely on the quality of your product alone.

- Opinion Leaders can translate the benefits and advantages of your produce into messaging that people understand.

- Opinion Leaders can help you understand the benefits and advantages of your product that are most salient to consumers.

- Different opinion leaders influence different customers.